Walter Deverell was amongst the circle (although not one of the original members) of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), a group of seven students who criticized the teaching of art in art schools, harking back to the rich colours and animated subject matter of Botticelli and other early Italian artists. Thus Lizzie was launched into a milieu completely foreign to her. Walter Deverell’s mother called on Lizzie’s family to assure them that Lizzie’s reputation would not be damaged by the modelling, as Mrs Deverell herself and her daughters would be present at all times. Her father worked as a cutler, and the children needed to work, but this did not mean that Lizzie leapt at the opportunity. In a scenario reminiscent of Tess of the D’Urbervilles, her father was engaged in a long and ultimately fruitless attempt to claim ownership of a convoluted family fortune. Lizzie had had a ‘respectable’, religious lower class upbringing. Lizzie Siddal (originally spelled Siddall but changed on her husband’s suggestion to make it look more genteel) worked in Mrs Tozer’s hat shop in 1849 when she was approached by an artist, Walter Deverell, who was looking for an artists’ model for Viola in a painting of Twelfth Night that he was working on. Lizzie Siddal’s life trajectory took her far beyond her origins, but she was always insecure and wary, and eventually succumbed to addiction. I might quibble with the supermodel concept, but certainly not with the designation of ‘tragedy’. In her subtitle ‘The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel’, Hawksley draws a not-completely satisfying parallel between Lizzie’s life and those of the supermodels of the 1990s.

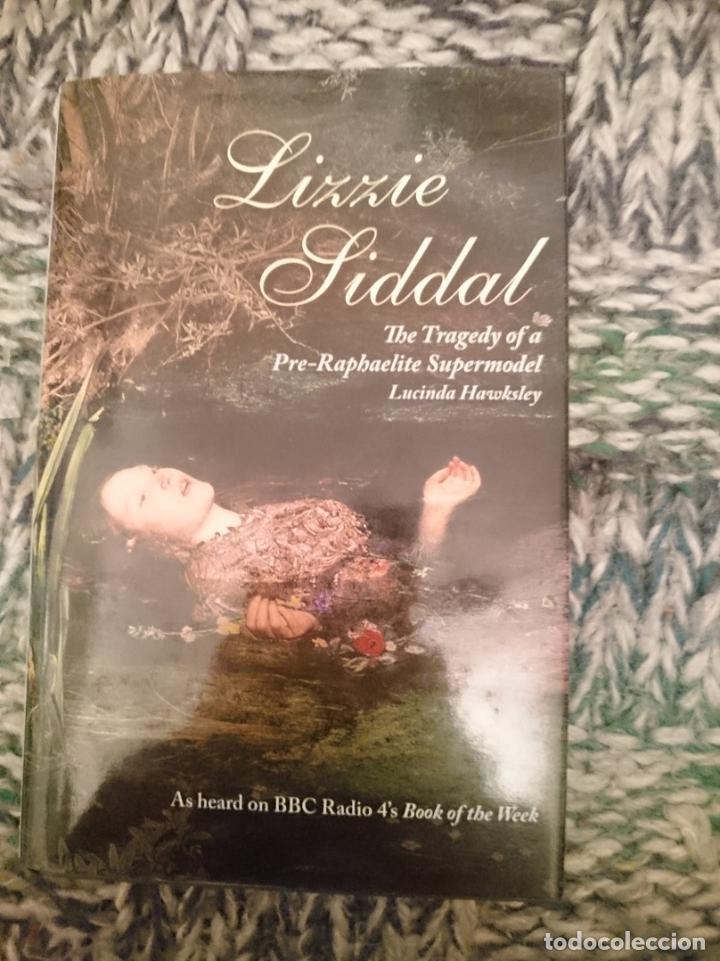

It is the image that Lucinda Hawksley has chosen to use on the cover of her book about Lizzie’s life. You will have seen her in John Millais’ painting Orphelia, deathly pale, her red hair flowing around her, her hands uplifted in supplication. You might not recognize the name, but you probably recognize the face of Lizzie Siddal.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)